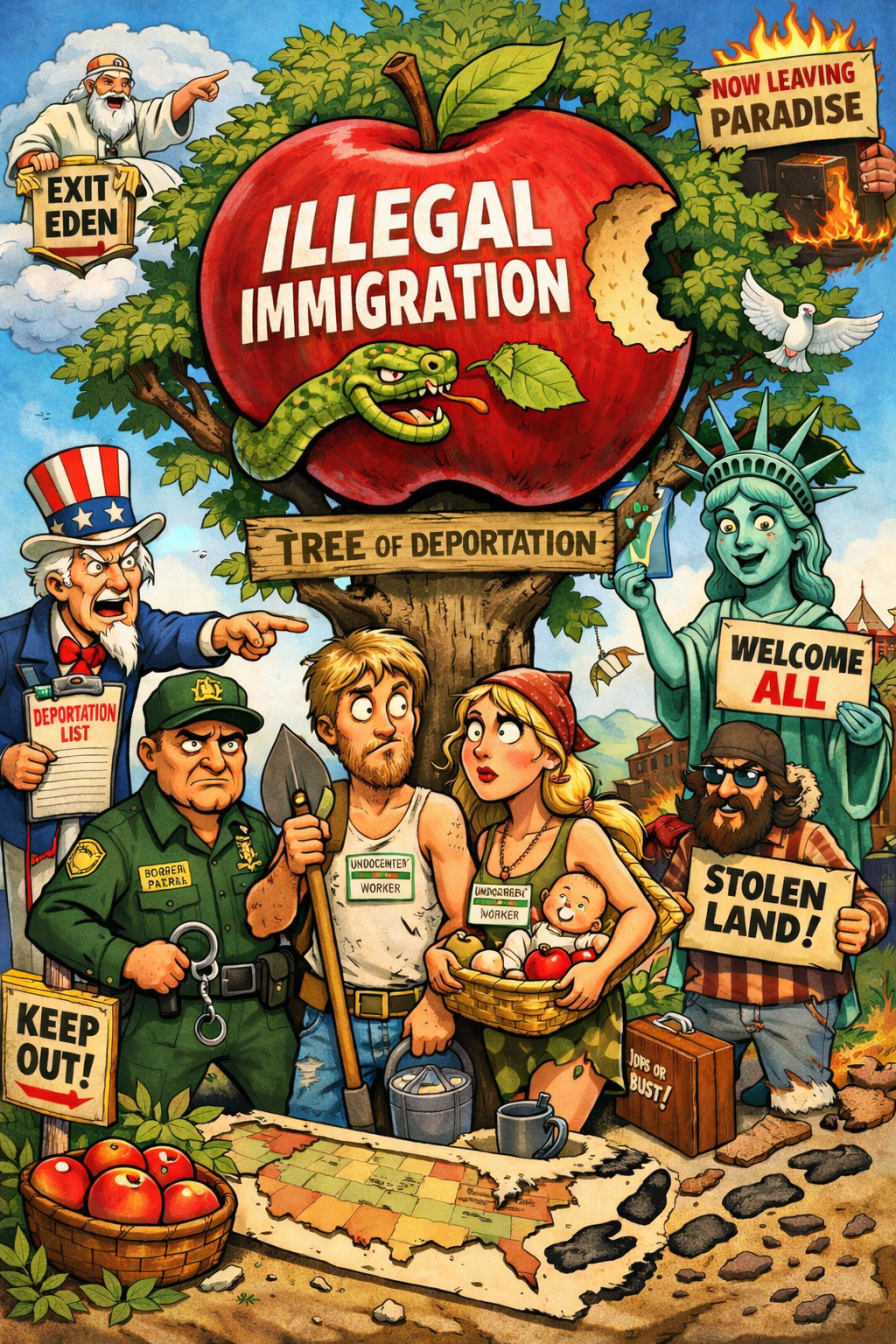

The Immigration Original Sin

The deportation debate keeps circling whether Trump promised to remove only “criminals.” That question misses the deeper disagreement. The real divide isn’t compassion versus cruelty—it’s whether unlawful presence itself carries moral weight.

The right generally treats being in the country illegally as the crime. Not because undocumented people are immoral, but because unlawful presence is a condition that doesn’t disappear through good behavior. In that sense, it resembles original sin: not a judgment of character, but a state you exist within. You can be lawful, loving, productive, and kind, and still bear the mark of original sin—being here illegally.

The left rejects that framework entirely. “There are no illegal people,” especially on stolen land. Illegality is viewed as a technicality that dissolves under human need and historical injustice. If there’s a biblical parallel, it isn’t original sin—it’s eating the fruit of knowledge.

Yes, it violates a rule. Yes, it leads to exile. But it also produces agency, self-awareness, and moral autonomy. The fall is painful, but enlightenment is worth the cost.

That’s why the two sides talk past each other. One side sees exile from Eden as the unavoidable consequence of defying a boundary. The other sees exile as proof the boundary itself was unjust, because Eden sat on stolen land.

This framing doesn’t deny the humanity of undocumented immigrants or the suffering caused by enforcement. Catholic theology never pretends exile is painless. It simply insists that compassion doesn’t erase original sin—it responds to it.

Until we admit we’re arguing over which story governs reality—obedience or awakening, order or agency—we’ll keep mistaking theology for policy and policy for cruelty.