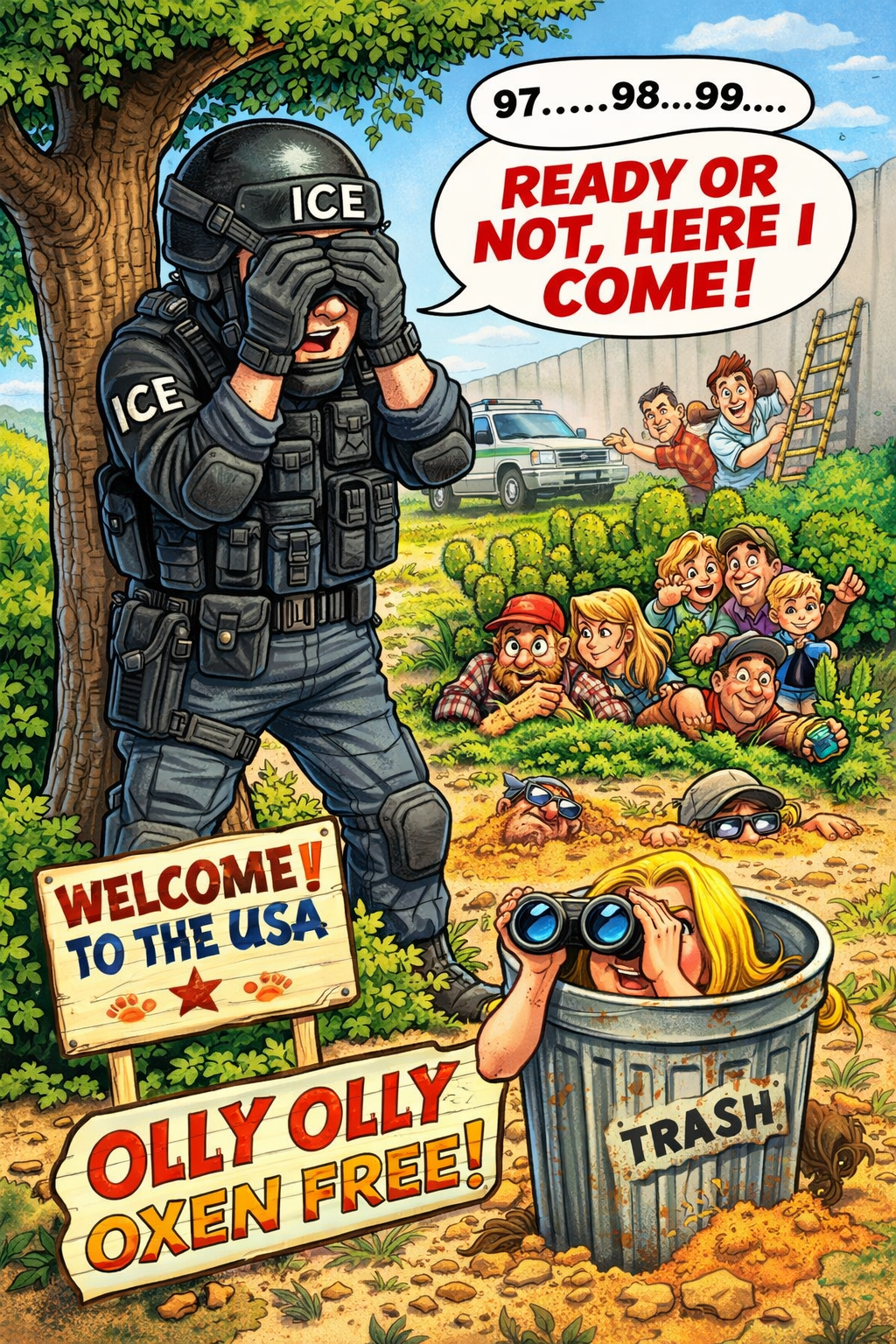

Olly olly oxen free?

Deportation in the United States can be modeled as a large-scale game of hide-and-seek shaped less by statute than by executive enforcement.

During periods of low barriers and low oversight—most visibly between 2020 and 2024—the system broadcast clear signals: enforcement was deprioritized, backlogs expanded, and risk appeared low. Migrants responded rationally. Advocacy networks and NGOs amplified the signal. Over time, many actors treated the quiet as permanence.

That was the mistake.

“Olly olly oxen free” was never called. It was inferred.

Executive orders are not law. They are contingent, reversible, and dependent on who holds office. This is why immigration policy is uniquely unstable: one administration builds a Jenga tower of tolerance through memos, guidance, and restraint; the next removes those blocks. DACA can be narrowed or revoked. Priorities can flip overnight. This is not betrayal—it is how executive power functions.

Claims that 20–40 million migrants entered during that period, or that 60 million undocumented residents now exist, may be inflated. But accuracy is secondary to perception. Belief drives behavior. Many people bet their lives on the assumption that “olly olly oxen free” had effectively been declared—and that future administrations would honor it.

That bet was never guaranteed.

When enforcement resumes, the correct description is not moral ambush but risk reactivation. A lapse is not an amendment. A backlog is not legal status. Time elapsed is not ratification. The rules did not disappear because they weren’t enforced.

The moral debate can continue. But descriptively, this outcome is what happens whenever actors mistake tolerance for permanence. If stability is the goal, it requires durable law—not inference, not vibes, and not pretending the seeker put the blindfold on forever.