On Paternalistic Racism

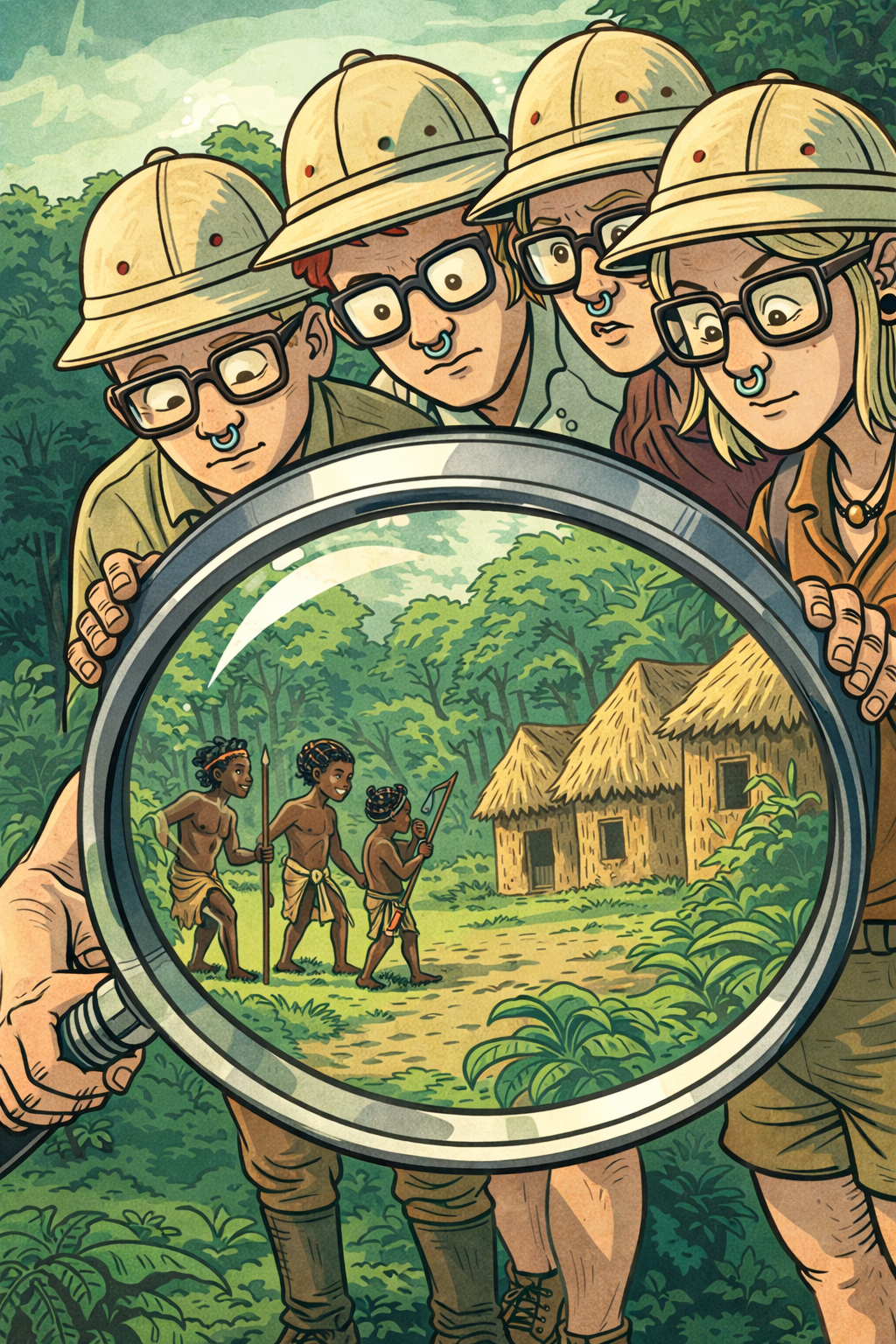

In social theory, paternalistic racism describes a pattern where individuals or institutions act to “protect” marginalized groups in ways that unintentionally reduce agency, complexity, or self-determination. Unlike overt prejudice, this framework is often motivated by empathy, moral responsibility, or a desire to prevent harm. The intent is typically sincere.

However, problems arise when protection becomes substitution—speaking for rather than with, assuming vulnerability rather than assessing context, or treating entire populations as if they share the same needs, risks, or limitations. In these cases, advocacy can quietly reproduce hierarchy by positioning the advocate as interpreter, guardian, or moral proxy.

Scholars note that this dynamic can resemble an anthropological stance: cultures and communities are treated as delicate, static, or best preserved rather than as modern, adaptive, internally diverse, and fully capable of navigating tradeoffs. While framed as care, this approach can unintentionally discourage autonomy, experimentation, or integration into broader social systems—out of fear that such engagement will cause disappointment, harm, or loss of identity.

An important aspect of ethical reflection is motivation awareness. When a person’s identity centers on protecting others—especially without being asked—it is worth pausing to ask why. Is the action driven by solidarity, or by unexamined guilt, displacement, or avoidance of one’s own unresolved responsibilities? Most often, the answer is not malicious. But without reflection, even benevolent actions can redirect agency away from those they intend to support.

A constructive approach emphasizes consent, reciprocity, and humility: listening before intervening, recognizing competence alongside vulnerability, and accepting that others may choose paths we would not choose for them. Treating people as full adults—capable of risk, error, adaptation, and modern life—is not abandonment. It is respect.