Was everything a lie? Maybe. Probably.

I was born in 1970. I didn’t live through the ’30s or ’40s, and I was too young to meaningfully experience the ’60s and ’70s as they happened. Everything I “know” about those eras came secondhand—school, parents, movies, television, books, documentaries, and later, prestige journalism. I absorbed history the way most people do: as a finished story.

What’s changed is living through a moment where I can see the narrative being built in real time—watching events unfold on the ground, inside cities, inside conversations, under full digital surveillance. The distance between experience and story has never been clearer.

If this were the 1940s, my entire understanding of World War II would have come from radio broadcasts, newspapers, and newsreels—much of it explicitly propagandistic. I listen weekly to radio from the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s, and the tone is unmistakable: noble boys, righteous war, mythic heroism. It wasn’t hidden. It was nation-building through story.

The same pattern exists in later decades. We talk about the ’60s as if radicalism erupted out of nowhere, but it didn’t. Allen Ginsberg wrote Howl in 1955—long before the Civil Rights Movement became mainstream history. The tremors precede the earthquake. By the time history notices, the culture has already shifted.

What’s unsettling now is realizing that once you start questioning one cornerstone narrative, the others wobble. If World War II—the moral foundation of modern American identity—turns out to be more sculpted than remembered, then what about World War I? The Civil War? The War of Independence? These aren’t just events; they’re load-bearing myths.

This isn’t denialism. It’s discomfort with certainty.

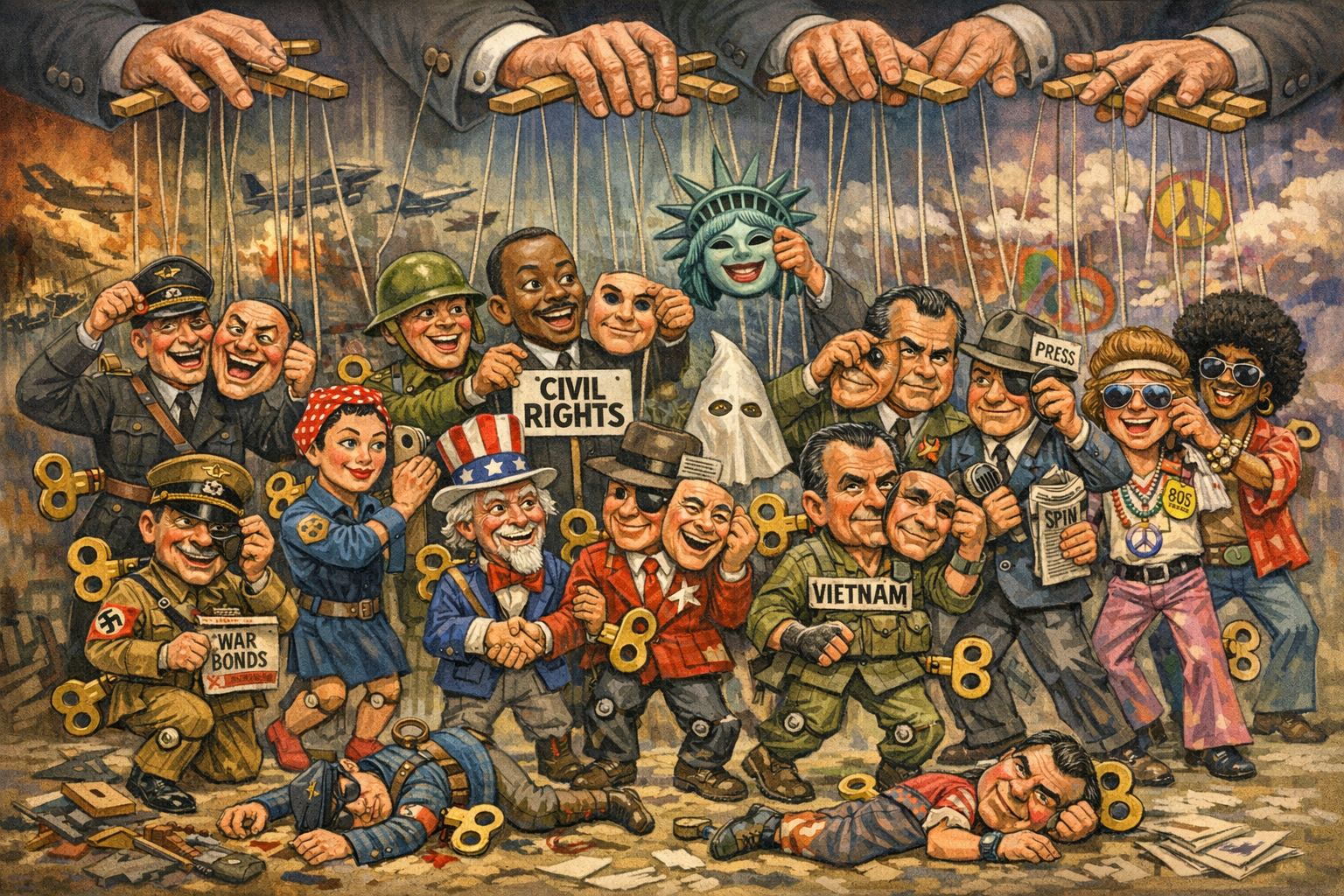

Once you see how stories are enforced—how dissent is framed, how counter-narratives are marginalized, how complexity is sanded down—you can’t unsee it. History starts to look less like a clean sequence of truths and more like a stage full of actors wearing masks, or puppets animated by unseen hands, repeating the lines that survived power and time.

That realization is destabilizing. It doesn’t tell you what didn’t happen. It forces you to admit how little you can be sure did. And once that scale falls from your eyes, inherited history stops feeling like knowledge and starts feeling like something closer to folklore—meaningful, powerful, but curated.

This is the first time I’ve seriously reconsidered how much of what I believe about America’s past is lived reality versus narrative inheritance. And I don’t think you can go back from that.